The following article was written by Marc Coseo, (National board certified licensed acupuncturist) for the Journal of Chinese Medicine.

When we force our bodies to bend and flex beyond normal limits, we damage ligaments and tissues that are essential to those movements. When stress of exercise or work demand more oxygen and nutrients than are available, or when circulation is inadequate to carry away the waste products of a stressed metabolism, tension, stiffness and pain are a common result. Tight muscles and inhibited circulation reduce flexibility and contribute to breaks and tears. Repeated damage leads to pain, reduced range of movement and in some cases, to problems requiring surgery. In the clinical setting we see these conditions in the form of tendon and muscle injuries or overuse syndromes. These typically require intensive treatment to overcome the biological inertia created by the injury.

For those who depend on their body to earn a living or have a propensity for physical activity, the associated pain and limitation of injuries or overuse can be extremely frustrating. This is understandable when one considers the stress associated with the inability to work or the frustration created by inactivity for those accustomed to an active lifestyle. Adding to the stress of injury are family responsibilities, financial concerns and logistical difficulties that prevent patients from keeping a sufficient treatment schedule. In cases where patients can only have acupuncture treatments sporadically, results tend to be substandard and the healing process lengthy. For improved results in these patients, I have found patient “homework” in the form of self-acupressure to be very effective.

Self-acupressure provides the patient with a means by which to control pain, ease muscle tension, increase flexibility and monitor progress. Done on a regular basis (I recommend at least three times per day), self-acupressure supplements the effects of acupuncture treatment and provides a self-treatment option to those who cannot keep regular appointments.

An effective method for self-stimulation of acupoints is the utilization of balls (rubber balls two and a half inches-65mm in diameter work the best) which are positioned so that the patient applies pressure to an acupoint by lowering his or her weight onto the ball(s). When acupoints are stimulated this way, the patient becomes aware of the “ache” associated with “obtaining the qi.” After applying pressure to the points from 20 seconds to 1 minute the ache gradually diminishes or fades away completely. Once the ache diminishes, the patient moves the balls to each of the next prescribed points until the entire point prescription has been stimulated. Acupressure positioning and exercises for major muscle groups are presented in my book, “The Acupressure Warmup”

The exercises there can easily be adapted to accommodate individual limitations and needs. For instance, if a patient needs to apply acupressure to the back but finds it difficult to lay on the floor, he or she can produce the same effects by sitting in a chair and leaning into the balls until the desired stimulus in achieved.

Research has shown that acupressure stimulates reactions that cause greater microcirculatory activity in the tissue bed, which in turn produces a more efficient movement of blood at the capillary level. This increases the availability of nutrients, and oxygen, and speeds the removal of the by-products of metabolism. In addition, the increased blood flow warms the muscle tissues. As muscle tissue becomes warmer, strength and flexibility increase. There are other physiological changes related to the increased production of biologically active substances, some of which influence aspects of the nervous system. However, from the patient’s point of view the immediate effect of pressure is a perceptible loosening and warming of the treated area, as well as a clear sense of increased relaxation.

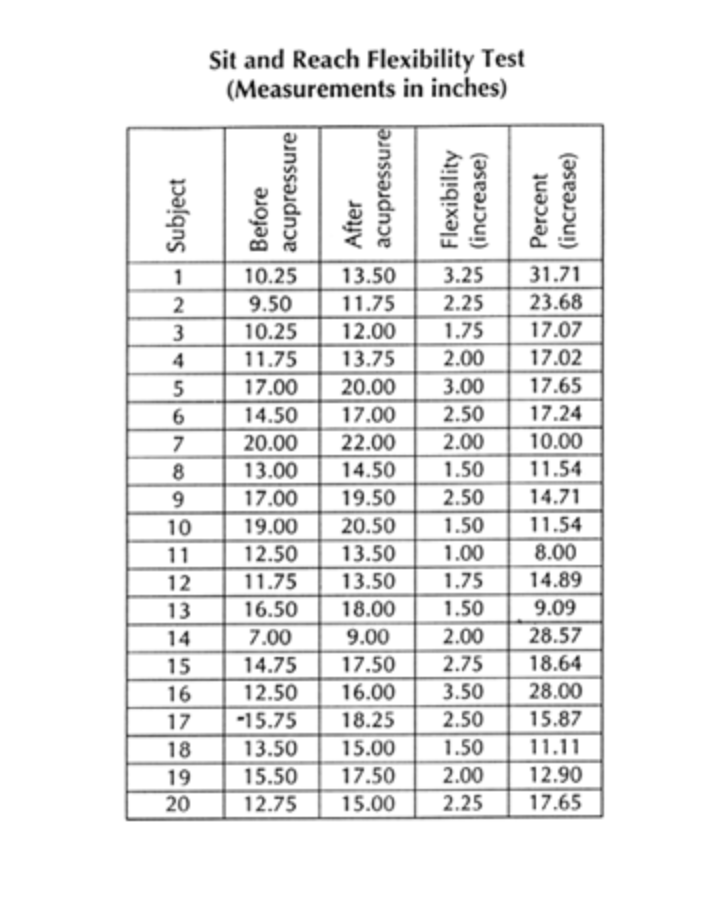

A study on the effects of self-acupressure techniques as a means for increasing flexibility was conducted using a group of 100 subjects ranging in ages from 14 to 72. In this study, subjects were instructed to self-apply acupressure bilaterally to acupoints #7, #8, #9, #10, #12, #13, #15 and #16 using rubber balls two and a half inches in diameter and after self-acupressure. Subjects were measured using the standard sit and reach flexibility test. All subjects showed an increase in flexibility ranging from eight to thirty one percent. A sampling of individual results is given below:

In our pioneering 1995 acupressure study, we laid the foundation for what would later become known as Ball Acupressure. We understand that many of you may be curious about the specific acupressure points we used in this groundbreaking research.

To make this information more accessible to you, we’ve created two different resources for you to explore:

- Whether you’re a visual learner or someone who enjoys reading historical insights, we’ve got you covered. We hope these resources provide you with valuable knowledge about the roots of ball acupressure and its specific applications.